"The goal of writing is to make others hear, see and feel."

following Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim

When and how did the Gotthelfts enter my life? Why have I been dealing with this German-Jewish family for more than 20 years?

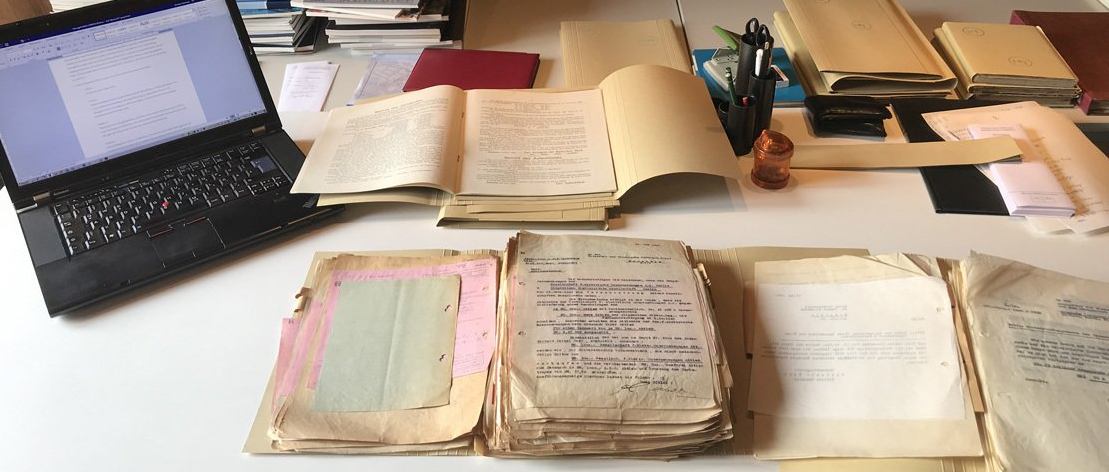

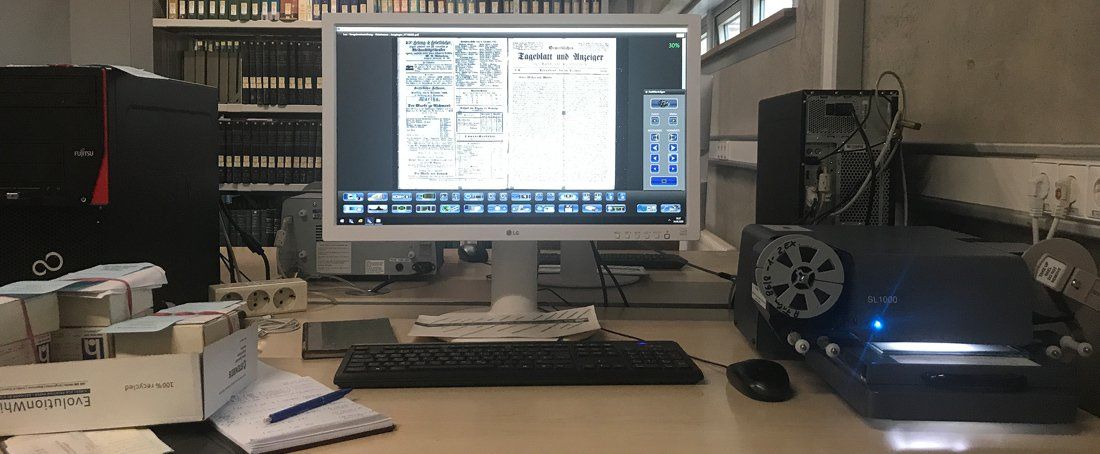

In 1998 I began researching my doctoral thesis on the writer Albert Rausch, who had also published under the name Henry Benrath. Rausch lived from 1882 to 1949 and was widely read until the 1960s. After that, he fell into oblivion - so thoroughly in fact, that there was hardly any research literature on him. The little I unearthed sounded more like legend than truth. So, I studied his books and delved into archives, reading for over a period of about 5 years several hundred handwritten letters by Rausch and to Rausch. Some were easy to decipher, wheras others required days of effort.

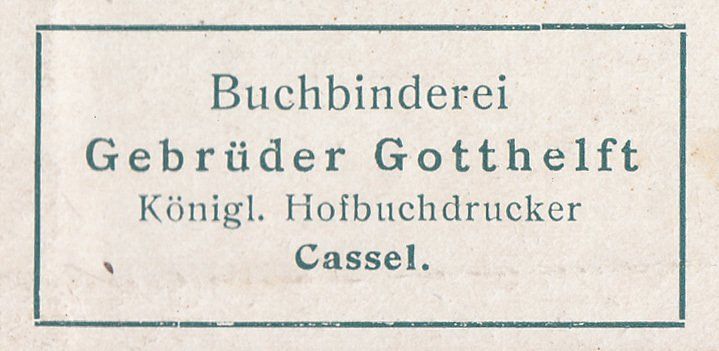

Gebrüder Gotthelft - Royal Court Book Printers

Parallely to the archival work, I searched for people who had known Rausch and who could tell me about him. And indeed: I was lucky! Through a long research- at that time still without the possibilities of the Internet- I succeeded in identifying two handfull of people. In Stuttgart, I met with his publisher, Albert von Haller and in a suburb of Genoa with Elisabeth Beeler. She had run the hotel where Rausch lived during World War II. In Chur I spoke with Peter Walser, the brother of a close friend of Rausch‘s and in Copenhagen with Paul Saft, who happened to be in a merry circle that had formed around the writer one evening and which did not end until the early hours of the morning. The two-day interview I conducted in Bad Sooden-Allendorf with blind Joachim Kohlhaas was very touching. The highlight of his life was his long-ago friendship with Rausch, about whom he still, after more than 50 years, spoke with rapturous enthusiasm. From Rausch's books, the letters and the reports of contemporary witnesses, I slowly, very slowly, formed myself a picture of the writer.

Reference to the Gotthelfts

The widow of one addressee replied to one of my letters. Her husband Kurt had died a few years earlier. She had not known Rausch herself, but Kurt had told her a lot about him throughout his life. She wanted to help me as much as she could and also wanted to give me the books that Rausch had given to her Kurt many decades ago, some with dedications. I accepted the kind offer, packed my suitcase once again and boarded the train to Bad Nauheim. Mrs. Fresenius told me the following on that hot midsummer afternoon in her summerhouse:

The elder Rausch was a fatherly friend of Kurt‘s. Together with Kurt and other young people, he had taken long hikes through the country around Friedberg and Bad Nauheim. Rausch knew the mountains and valleys of his homeland better than anyone else. Along the way, Rausch spoke about the history of the region and the importance of art in a person's development. The son of a Jewish family also took part in these tours that sometimes lasted several days. Gert, like her Kurt, had already passed away, but his sister Adelheid was still alive in London. Certainly she had known Rausch personally. He had always been going in and out of her parents' house. By the way: In Rome there was also Stefania, a cousin of Adelheid. Both ladies were very old, some over 80, I should hurry... Mrs. Fresenius wrote down the two addresses and thus changed the course of my life.

Again I wrote letters, and the contact with Stefania in Rome succeeded first. We agreed to meet in Switzerland, halfway between Germany and Italy. Stefania wrote that she would spend her vacation in Zermatt. We would meet there at a restaurant. As a sign of recognition, I was to hold a book by Rausch in my hands.

First meeting with Stefania

A few weeks later I sat on the terrace and waited. I imagined how the 80-plus-year-old woman would enter the terrace taking short steps, as old people do, perhaps leaning on crutches or a walker and looking around thoughtfully, looking for a man with a book. Thoughts went back and forth in my head: How should I break the ice? How do I, as a German, deal with a Jew who had fled from the Nazis to Italy at the age of 17? - I had already found this out from Mrs Fresenius. I knew Jews only as artificial figures from television, theater or books: Shakespeare's Shylock, Lessing's Nathan, Freytag's Itzig, the Weiß family from the Holocaust series.

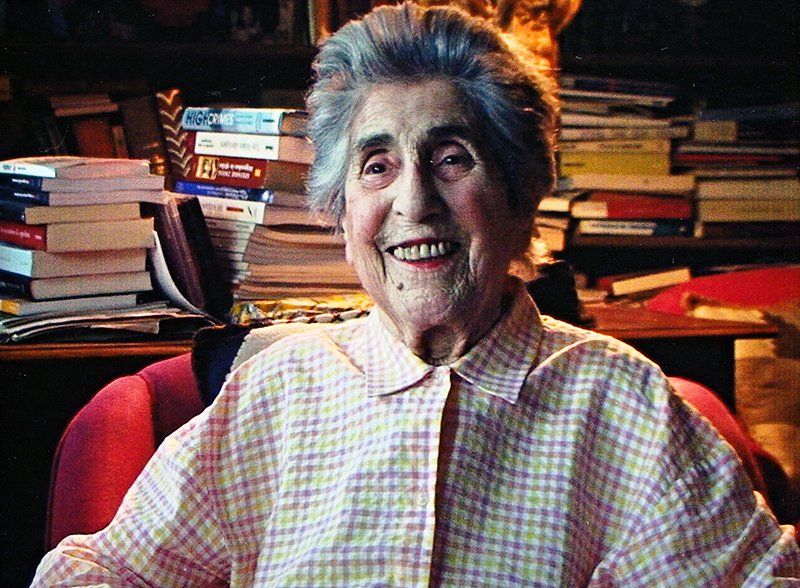

And suddenly Stefania was standing in front of me! With sweeping steps she had stepped onto the terrace of the restaurant: Knee breeches, woolen socks, hiking boots, plaid shirt, a felt hat perkily set on her head, a walking stick in her right hand and a small backpack in her left. Alert and wise eyes peered out of a finely cut face. She sat down and a load fell from my heart. There was no ice to break between us, for she immediately chatted away and was completely natural. She had been on a small mountain tour, not to be compared with the long hikes of earlier days, but still a decent distance for a woman of 83. Although she had spent several decades abroad, her German was still excellent, completely without accent.

Stefanie during the interview in her apartment in Rome.

I asked about Rausch. She could recall the writer's frequent visits to her parents in the 1920s and early 1930s. She described his dress, his appearance, his manners, how he carried on conversations on the terrace where coffee was drunk in the afternoon. What she said confirmed completely the impressions I had gained of Rausch's personality from letters and accounts of other contemporary witnesses. I did not learn anything new.

After everything had been said about Rausch, there was a longer pause. I thought about it: Should I already say goodbye? No, that would have been impolite... One question had been on the tip of my tongue for some time: How could a woman who had fled her homeland at the age of 17 and had certainly been through a lot of difficulties, perhaps even terrible things in her life, radiate such cheerfulness and contentment? I took heart and asked the question. Stefania smiled and answered:

“In order for you to understand that, I would have to tell you a lot, basically my whole life. Do you really want to listen to all that?”

What I got to hear in response to my “yes” in this and two following encounters, sparked me. That afternoon in Zermatt the German-Jewish Gotthelft family entered my life. Since then, the Gotthelfts and their eventful history, which reaches over three hundred years into the past and continues in the present, have accompanied me. They have remained a constant in my life and to which I devote myself after work of my bread and butter job: in the evenings, on weekends, on vacations – sometimes more, sometimes less intensively, as external circumstances and inner forces allow. An end of my occupation with the Gotthelfts is not in sight.

Stefania's trip to Italy

Stefania began telling her story in the year 1933. Hitler had taken power in January. In Kassel where the Gotthelfts were from, an SA squad abducted two Jewish lawyers at the end of March and mistreated them for hours in the worst possible way. One day in April the parents said to Stefania:

“The day after tomorrow, you're going to Lily's for three weeks. The change of air will do you good!”

Lily was Stefania's older sister and she was spending her semestera broad in Italy, at the University of Perugia. Lily was open, extroverted a conquerer of the world. Stefania was the exact opposite: shy and quiet, daydreaming in a shell. Her parents' announcement frightened her: a train trip, unaccompanied and abroad at that!

Passengers got on and off. Stefania wanted to make herself invisible in front of the new and unknown faces. She pressed herself deeply into the cushion of the backrest and with her arms crossed, looked through the window. She did not lift her eyes when the compartment door opened and closed again. In that manner she went out of Germany and through Switzerland into Italy. At every border control she trembled before the officials and their harmless questions about where she came from and where she was going.

At last she is alone in the compartment. Sometimes the train travels at walking pace through the stations of smaller towns and villages. She opens the window, sticks her head out and hears snatches of a soft, melodic language. She sees the hand movements with which people accompany their words. Months later, someone will say to her:

“You must learn to speak with your hands as well, only then will you fully belong.”

For the first time she feels something like joy regarding the three weeks with Lily. Soon she will be with her big sister. The train stops on an open track. She waves almost cockily to the farmers in the field. They wave back, wearing headscarves or caps. She smells fresh grass and water of a nearby river.

In Perugia, she gets out of the compartment with her suitcase. She looks around and already sees her sister rushing towards her, feels her embrace and her kisses on cheeks and forehead. Lily, the whirlwind! Before she can express in words her joy at their reunion, she hears Lily say.

“You're not going back! You're staying here with me in Italy. You're in emigration now.”

The news hits her completely unexpectedly, like a bolt of thunder from the sly. For a few seconds, she stands motionless and in silence. Thoughts swirl in her head and a rush of feelings in her heart, a mixture of helpless helplessness, abysmal despair and infinite indignation at her parents and sister who – secretly and without asking her – had decided about her and her life. Lily's comforting and encouraging words do not penetrate her consciousness. She sees the lip movements, but she does not understand what they say.

The image of the young woman, who was still almost a girl, standing distraught on a platform in a foreign country, unable to imagine how her life should continue, did not leave me for days and weeks after our conversation in Zermatt. Stefania was suddenly faced with nothing and with challenges for which she was not at all prepared. She was still attending school, had learned nothing practical! How could she keep her head above water, how could she provide for accommodation, food and clothing? She didn't speak Italian, didn't understand what was being said to her, words and phrases on signs and information boards made no sense to her. In Europe today you can almost always get by with a little English. It was very different back then. And smartphones and computers with software programs as translation aids, were still beyond anyone's imagination

For months, Stefania's only means of communication with the world remained her sister, who could hardly empathize with her: with her shyness, with her shyness in front of strangers, with her difficulties with a foreign language, with her fear of expressing herself after she had mastered a few words. Again, Lily was quite different: she had a talent for languages and had already learned a fair amount of Italian during her stay in Perugia. If she didn't know something, she just talked away, hoping that the listener would understand what she meant. Stefania on the other hand, had a hard time, an infinite hard time, not only with the language, but with everything. In her darkest and bleakest hours, she felt cut off from life, as if she were in complete isolation that would never end.

On the trail of the Gotthelfts - for over 20 years

The story of the young woman who woke up in Germany in the morning and went to bed in Italy in the evening without finding sleep, because her life had been completely upset, gripped me. For the first time I had before me a person whom the regime counted as one of its enemies, because she came from a Jewish family. Until then, words like „persecution“ and „persecuted“ had simply sounded abstract.... Naturally I wanted to know how Stefania's story continued, how she managed to gain a foothold in Italy, to survive when the persecution of Jews began there as well. What had happened to her parents in Germany? What had happened to Lily? And: What kind of family were these Gotthelfts anyway? What kind of people were they? Where did they come from? What had they achieved? How had they shaped their lives? How did they achieve renowness - and not only in Kassel? How rich, how exciting, how fascinating and how moving the history of the Gotthelfts was, even in the times before 1933 and after 1945, became clear to me only in the course of the years. I had not even the faintest idea of this, when Stefania, back then in Zermatt, told me about her trip to Perugia - and no idea of how much the Gotthelfts history is the history of Judaism in Germany.

Through kinship the family was connected with important Jewish personalities. Among them were: Bertha Markheim (1833-1919, confidante of Karl and Jenny Marx), Julius Rodenberg (1831-1914, journalist and writer), Alfred Apfel (1882-1941, criminal defense attorney and board member of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Religion /Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens), Ottilie Schoenewald (1883-1961, politician and women's rights activist), Irene Eisinger (1903-1994, soprano), Otto Loewi (1873-1961, pharmacologist and Nobel Prize winner), and Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929, historian and philosopher).

TO BE CONTINUED...