Introduction

To begin the foreword with Bertha's end would shift the perspective. Bertha was more than a persecuted victim of National Socialism.

She was an actress at the best theaters in the German-speaking world and thrilled moviegoers in the first half of the 1920s under the stage name Sybil Morel. She was an author and wrote a novel that was ruthlessly critical of the film industry: Love on the Soundstage

after the end of her screen career.

I am placing this book at the beginning of my short biography of Bertha, who was born in 1892 and murdered in a Nazi extermination camp in 1942. As you can see from the dates, 2022 was the 130th anniversary of her birth and the 80th anniversary of her death. This is the reason for me to publish the novel as an ebook: to commemorate Bertha and her extraordinary life which began in the German Empire, culminated in the Weimar Republic and violently ended under National Socialism.

Love on the Soundstage

was published in 1933 by Karl Goldmann Verlag in Berlin. The novel is a slim volume of 200 pages. The title words appear in red cursive script on a cover jacket taken from a photo out of a movie: A distinguished couple sitting together in a café or restaurant, drinking champagne and gazing lovingly into each other's eyes. The text under the photo promises the reader an enchantingly beautiful woman as main character of the novel, insights into the lives of screen stars and into the glamor of the film world.

Cover and blurb for Bertha's novel. The movie scene has been retouched for copyright reasons.

During Bertha's lifetime, cinema had become a huge success. In her childhood, moving pictures on celluloid were still a sensational novelty.

When stars arrived, fans flocked to the stations in droves. At autograph sessions, queues formed several hundred meters long. Photographs of directors, actors and actresses hung in people's homes. Newspapers and magazines regularly reported on every step and every utterance of screen darlings, some of whom were almost idolized. When Rudolph Valentino's coffin passed through New York in September 1927, hundreds of thousands lined the streets. In some places, crowds on the sidewalks were so thick that shop windows were broken.

Spectators at fairgrounds and funfairs marveled at the living photographs. Unpretentiously entertaining short clips could be seen for a few pennies. Barely 20 years later, when Bertha stepped in front of the camera for the first time, 100 companies were already producing around 300 full-length feature films in Germany a year, which - together with foreign films - satisfied the public's hunger for always new light shows. In the early 1930s, as Bertha made her last films, 2,000,000 viewers visited German cinemas daily, which sold 730 million cinema tickets annually! By comparison, just 117 million tickets were sold in Germany in 2019.

This background explains the hunger for entertainment literature on the subject of cinema. Bertha's Love on the Soundstage

is one of around 70 titles that appeared in the book market between 1913 and 1933. Further fodder was provided with serialized stories in journals, newspapers and magazines. The writings dealt with how to find a way to film; being discovered, stardom and star hype, the conflicts between rival actresses and actors, affairs between directors and actresses, affectations and scandals

However, that did not exhaust its content: in the 1920s feature-length films with self-contained plots and elaborate sets and costumes were a a new format whose condition of creation still aroused the curiosity of viewers. What we take for granted today had an aura of mystery back then. This is why the more or less sophisticated literature that took cinema as its subject, also gave ist readers insight into film production. What did the director's work in a studio consist of? What did a cameraman, who was called an operator at the time, have to do? What were the tasks of an editor? Which techniques were used to achieve which effects?

At first glance, the cover and advertising text suggest that Love on the Soundstage

seamlessly fits into the cinematic literature just outlined. Indeed, Bertha's novel is part of literary mainstream - and yet it stands out from it. One of the most important features is: the novel was not written by someone outside the industry who had only a superficial or second-hand knowledge of it, its structures and rules. Bertha was an insider, who had appeared in around 50 leading and supporting roles in front of the camera between 1918 and 1932 and was intimately familiar with the light and dark sides of film business.

Advertisment in the Neue Mannheimer Zeitung of

december 10, 1927 for Heilige Lüge (US title The Scared Lie)

december 10, 1927 for Heilige Lüge (US title The Scared Lie)

She included her experiences in Love on the Soundstage. The novel about Lotte Werder, who breaks out of her middle -class life style to become a film star describes young women’s immense attraction towards the film industry, the struggle for roles, the shooting preparation in film studios, the shoots under hot spotlights, the travels to exotic locations abroad, the footage editing that fonally becomes a finished film, the premiere screenings in huge cinema palaces, the stars on red carpets in a flurry of photographers' flashes, the cheers of audiences after a performance. Bertha embedded countless details from her career as an actress into the plot. This is exemplified in the chapters in which Lotte visits the Berlin Film Ball, spends time filming in Romania or meets fellow actors, which Berta modeled after her former film partners.

Love on the Soundstage differs from other cinema literature, not only because the author was part of the industry and therefore an intimate connoisseur of it.

As a rule, the novels were written by unattached women who wanted to enter film business to become movie stars. Not so with Bertha: Lotte is married and the mother of a young daughter. She sees her screen career as an opportunity to raise much-needed money to support her family. To do so she leaves her loved ones in a dispute, because they are against her plans. For its time, this story is unusual, as many readers saw the main task of a married woman as supporting husband and children.

Bertha's novel is also exceptional because it sheds detailed light on the dark sides of film business. As far as I know, no other narrative work from the 1920s and 1930s is so mercilessly critical of the film industry. In Love on the Soundstage

the industry is primarily sales-oriented and geared towards the production of films as mass-produced goods. Actors and actresses are means of production, helplessly dropped and replaced as soon as the industry no longer needs them. The novel also looks at extras and those who have to beg for the smallest roles every day in order to make ends meet. If their efforts are unsuccessful, they face unemployment and social decline.

Lotte's darkest experience in the film industry arrives when she is stalked and assaulted by the director who had discovered her.

Fred Koster regards Lotte as fair game who has to be sexually submissive to him in return for a career opportunity. The ruthlessness with which Koster exploits his position of power in the industry to subjugate women to his sexual desires, is reminiscent of those film powerhouses

whose sexual misconduct was exposed by the Me Too movement a few years ago. As more and more women all over the world came forward who had experienced similar assaults and coersions, it led to public awareness that sexualized violence in the male-dominated film industry was a global phenomenon and an open secret.

The so called casting couch

has a long tradition. Even in Bertha's day it was known in the film industry that decision-makers demanded sexual acts from women in exchange for career opportunities or employment. However, even then there was silence on this hot topic. Contemporary films and books alluded to it at best or dealt with it episodically, e.g. Rosa Porten's Filmprinzeß

(1919), Walter J. Bloem's Tanz ums Licht

(1925) and Stefan Szekely's Die große Sehnsucht

and Grete Garzarollis (i. e. Grete Scheuer) Filmkomparsin Maria Weidmann

(1933). As far as I know, Bertha was the first to make this subject her main topic. It is obvious that Bertha's novel is primarily concerned with Lotte's Me Too experience; the rest of the story is of secondary importance. Bertha describes in detail how Koster stalks her, how he lays his traps and finally assaults her. Whether and to what extent, Bertha also here incorporated her own experiences into the novel, cannot be determined on the basis of current source material.

With Love on the Soundstage

Bertha looked back in anger on her fourteen years in the film industry. Bertha must have realized while writing that the novel would be seen by the industry as a way of getting even and that it would turn her into a nest-soiler. There could be no going back to the camera.

Bertha's life before and after her film career is also worth a closer look.

In my biographical sketch, which I will continue on this website at irregular intervals, I show how Bertha managed to fulfill her lifelong dream of becoming an actress, despite an early stroke of fate; how she trained as an actress, how she embarked on a stage career, how she ended up in the film business, how she filled movie theaters for a few years as a screen star, how role offers became fewer and far between and how, at the end of her career, Love on the Soundstage

emerged. In corresponding chapters, I explain in detail which elements of the novel's plot were inspired by which experiences in Bertha's life and which historical personalities were an inspiration for her characters.

In the last chapter of the biographical sketch, it will read that Bertha was one of those Germans, who had the misfortune of being defined as Jewish by National Socialism. For this reason she was stigmatized, disenfranchised and ostracized by the Nazis and their helpers in the 1930s. Bertha did not flee from the pressure of persecution by emigrating, she remained in Germany. In 1941 eight years after the release of Love on the Soundstage

the Nazis and their helpers deported her from Berlin to the Polish ghetto in Łódź. There, the once celebrated actress survived an autumn and a winter of hunger and cold, before she was murdered in the Chełmno extermination camp in May 1942.

In the forest of Rzuchów, near the Chelmno extermination camp: mass grave

Picture: Christian Hartmeier 2022

Bertha left her mark as an actress. Her name has been preserved on theater tickets and movie posters, her appearance in magazine photos and her acting performances in critics' reviews. Three important film productions in which she took part are available on DVD (Opium

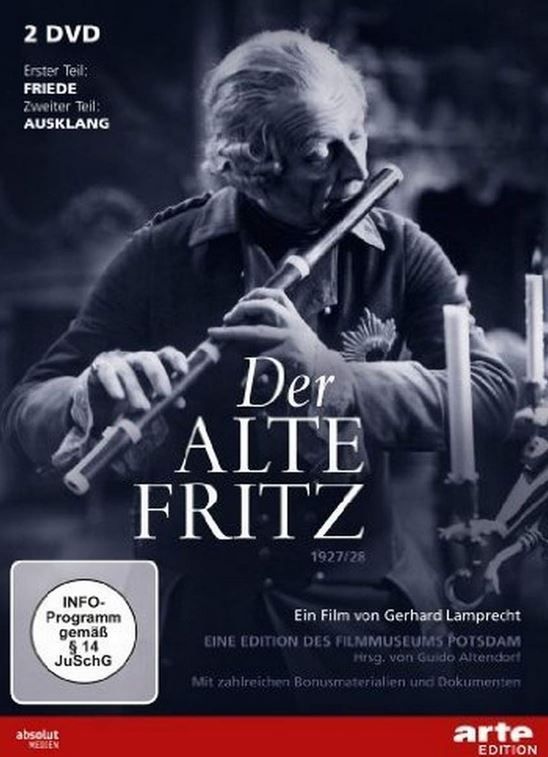

[1919], Der alte Fritz

[1928], Unter der Laterne

[1928]). Her novel is available again as an e-book - and here is my biographical sketch. Bertha’s memory lives on.

Opium

(world premiere december 15, 1919), leading role, Sin/Magdalena

Unter der Laterne (world premiere september 4, 1928), supporting role, The Old Woman

Der alte Fritz - Friede (world premiere january 3, 1928), supporting role, Mrs. Enke

Click on the covers to go to Amazon!

Unter der Laterne (world premiere september 4, 1928), supporting role, The Old Woman

Der alte Fritz - Friede (world premiere january 3, 1928), supporting role, Mrs. Enke

Click on the covers to go to Amazon!

The situation was different for women, men and children who were deported from Berlin together with Bertha. With a few exceptions, they were unable to attract attention to themselves. They were ordinary people who were of no interest to anyone beyond their circle of family and friends. Their names can only be found in the deportation lists of the perpetrators. That is why I would like to use my biographical sketch to remember all the Jewish Germans who had to join Bertha on the journey to the ghetto on an October morning in 1941 and thus to almost certain death: the worker Fritz Walter Salomon, the accountant Dora Kurzweg, the tailor Aron Geizmann, the glazier Simon Ehrmann, the nurse Else Rothschild. I will mention the names of the 1084 deportees later in this article.

I first came across Bertha many years ago in the family tree of the Jewish Gotthelft family, into which she had married.

I have been researching the Gotthelfts, who ran a print shop and published a daily newspaper in Kassel, for a good quarter of a century. Only about 2 ½ years ago I found out from Ulrike Emigh, the granddaughter of Bertha's divorced husband Ernst, that Bertha was actually Sybil Morel, a movie star of the silent film era.

I originally planned to have the novel and the short biography published in 2022, on the 130th anniversary of Bertha's birth and 80th anniversary of her death. However, the ambitious schedule was impossible to keep, as I could only devote myself to Bertha part-time, i.e. after work, at weekends and on vacation. I also researched and wrote on commuter buses, on my daily journeys to and from work. I would have liked to dig much deeper into archives, but there was simply not enough time. The lack of factual specialist literature proved to be a further difficulty. The little that can be found on Bertha is so riddled with errors that I couldn't rely on it. So I started almost from scratch.

I was able to research some things, but not others. I tried to fill in the gaps by reconstructing a possible past. An example of my approach are the passages about Bertha's childhood in Mannheim. First, I used address books to find out where Bertha lived, then I used city and building plans and pictures to find out what she saw and heard. Finally, I visited the places to gain personal impressions. My reconstruction also incorporated typical ways of thinking, behaving and living of the social class in which Bertha grew up. This gave me an approximate picture of Bertha's childhood in Mannheim at the turn of the century. To reconstruct other parts of Bertha's life, I drew on diaries and memories of contemporary witnesses who had experienced similar things. Knowledgeable readers will easily recognize that my descriptions of Bertha's discrimination, which she faced as a Jew in Berlin in the early 1940s before being deported, are based on the notes of Edith Marcuse. The sister of the writer and philosopher Ludwig Marcuse lived with her mother - like Bertha - and in her diaries she vividly recorded the everyday life of Berlin's Jews under the regime’s persecution.

My biographical sketch is no more than a first approach of Bertha. It would be a great satisfaction to me, if my work were to motivate one or two readers to take a deeper and more detailed look at Bertha. I am convinced that there is still undiscovered material lying dormant in archives and on the Internet, the analysis of which would clarify, expand and certainly also correct my findings.

I would like to thank the following women for their contribution to the Bertha/Sybil project:

Silvia Benuzzi, Wilhelm Gotthelft's great-granddaughter, organized and coordinated the filming of feature films and television series for Italian television for almost 20 years. Our conversations showed me that many aspects of Bertha's novel are still relevant 90 years after its publication. Silvia's contribution to the Bertha project also consisted of translating Liebe im Tonfilmatelier into Italian. The e-book in this language is planned for January 2025.

Katarzyna Bareja accompanied me to Poland as my driver, interpreter and conversation partner. In Łódź we went to the former ghetto in search of traces, as well as to the Chełmno nad Nerem extermination camp, where Bertha and her mother Adelheid were murdered. Without Katarzyna's commitment, the trip would have borne much less fruit. A report about our days in Poland can be found here.

Chapter 1 will appear when the translation is finished.